The Forgotten Students Behind Brown v. Board of Education

To commemorate the 67th anniversary of the U.S. Supreme Court ruling on school segregation, here’s another look at my 2014 Q&A. with Justin Reid, then associate director of the Moton Museum.

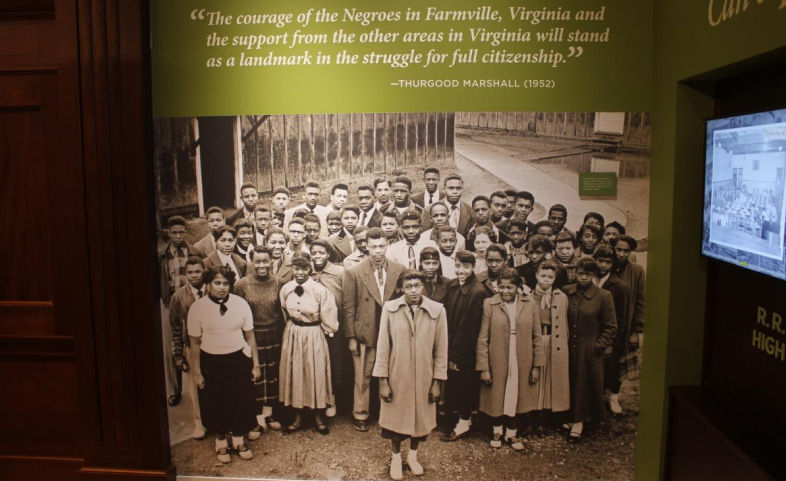

In 1951, black students in Farmville, Va., — led by 16-year-old Barbara Johns — staged a strike to protest conditions at Robert Russa Moton High School. The subsequent lawsuit later became one of five cases folded into Brown v. Board of Education, the landmark desegregation decision by the U.S. Supreme Court that made “separate but equal” unlawful. Moton was the only one of the five cases that began with a student-led challenge.

The Moton students’ struggles didn’t end with the May 17, 1954 Supreme Court ruling, now marking its 60th anniversary. Rather than comply with the court, Virginia lawmakers launched a campaign known as “Massive Resistance,” and in the fall of 1958 closed schools in three major districts for a semester to avoid having to integrate them. Prince Edward County – home to Farmville — shuttered all of its public schools in 1959, and they remained closed for five years. During that time, white students attended private academies paid for by their own families and sympathetic segregationists. But black students were left largely to fend for themselves, cobbling together educations in church basements and home-school settings.

In 1963, a coalition of educators and community leaders created the Prince Edward Free School Association, and used private funds and the support of President Kennedy’s administration to open four campuses serving about 1,500 black students. The 1964 Supreme Court ruling in Griffin vs. School Board of Prince Edward County forced the district’s schools to finally reopen.

The Moton School is now the Moton Museum and a National Historic Landmark, its classrooms turned into exhibits documenting the students’ strike, the five-year educational drought, and the legacy of the historic Supreme Court ruling. I spoke with Justin Reid, associate director of the Moton Museum, about the Brown v. Board anniversary.

When people talk about Brown v. Board, it’s usually thought of as one court case. But the Moton students actually accounted for 75 percent of the plaintiffs. So why wasn’t Moton the lead case instead of Brown (a class action consisting of parents and students in Topeka, Kan.)?

The court wanted this to be seen as a national issue, and not a southern issue. Justice Earl Warren, the former governor of California, had been appointed to the Supreme Court just two months prior to the desegregation ruling being handed down. He encouraged the other justices to make it a unanimous ruling. In his mind, the way the decision was handed down was as important as the decision itself.

What was it like to be a student at Moton in the 1950s?

The primary issue was the school was too small. It had been built for 180 students and they had more than 450. Classes were held in farm buildings and chicken houses — the same structures you would put an animal in. Students had to hold umbrellas when it rained because the roof leaked so badly. There would be one pot-bellied stove, and in one part of the room you’d be burning up and in another you’d be wearing your winter coat and shivering because the heat didn’t reach that far. Students from those years talked about how often they missed school because they were sick.

Farmville High School, for the white students, was only a couple of blocks away so there was something to compare to. Moton had no cafeteria, no gym, no science lab, no lockers, no teachers’ break room, no infirmary. Right up the street they could see all the things they were being deprived of.

Moton students weren’t just striking for equal buildings, they were striking for an expanded curriculum to prepare them for the workforce and college. They knew education was important, and they would do anything they could to get a quality one.

When the free schools opened in 1963, some students had been studying on their own while others had been without schooling of any kind for several years. The decision was made to group them by ability, rather than age. Are there lessons for educators today from that and some of the experimental approaches taken by the free schools?

Many of the things being done in the free schools that were considered radical at the time are now being used to try and close the achievement gap. The non-graded school system was certainly one of them. You can’t assume a child knows something because of their age, you have to meet them where they are and start there.

There were also very small class sizes (in the free school) – 15 students to every teacher. There was extended learning time, after-school programs and Saturday schools. Students had access to wraparound services: basic medical care, free breakfast and lunch. Those things are fairly commonplace now but they certainly weren’t back then. It became possible only through public-private partnerships, the kind of cooperation many schools and communities are trying to build today.

Are we giving the right amount of weight to the Supreme Court ruling as part of the broader narrative about the Civil Rights Movement?

The popular narrative is that Brown v. Board was the catalyst for the entire Civil Rights Movement. But that’s an oversimplification. The Supreme Court didn’t just wake up one day in 1954 and decide to desegregate schools. There was a massive grassroots effort that led to that decision, including two decades of legal action.

The Brown decision itself was a huge step forward: It shifted the way we viewed race as a society, and it helped us to begin to challenge what many people had long considered acceptable. But in some ways, Brown was a step sideways. The Supreme Court said in 1954 that schools should be integrated, but in the following year the court allowed the opponents (of desegregation) to frame the process.

If we’d had leadership who said, “We’re going to do this and make it as easy as possible,” instead of fighting every step of the way, we might have seen a much different outcome. Instead, we had white families who felt compelled to leave the public system for private schools, because that’s what the Southern leadership encouraged them to do. The racial tension was nurtured.

Does it surprise you that most people don’t know about Moton?

It’s not a surprise at all, unfortunately. Students who visit the museum often ask me “Why haven’t I ever heard about this?” The only people they ever learn about are Rosa Parks, Martin Luther King Jr., and Malcolm X. But the Moton legacy is actually a useful way to help students relate to that period in history. They can see themselves in the strikers and relate to Barbara Johns, the 16-year-old Moton Strike organizer who spoke up because she believed something was wrong.

It’s important to know that desegregation happened in part because students were part of the movement and were doing things that some adults were afraid to do. It’s a reminder to young people that they, too, can bring about change.