Charter school advocates and skeptics speaking at a recent Education Writers Association convening for Spanish-language media agreed on little except this: Charter schools are having a big impact on Latino communities nationwide.

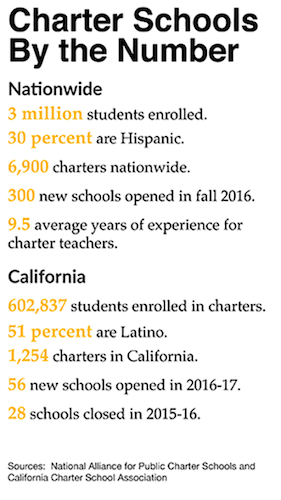

The number of Latino students enrolled in charter schools has grown rapidly. In 2004, they represented 21 percent of charter school students; now the figure is 30 percent, according to the National Alliance for Charter Public Schools. (By comparison, one-quarter of students in traditional public schools are Hispanic, federal data show.) This comes as the charter sector has grown substantially over the past decade, now serving some 3 million students. (See chart.)

The debate continues, however, on how well charter schools are educating Hispanic students and whether they are spurring innovation in traditional public schools. Below are highlights from four speakers who participated in a discussion of charter schools at the EWA convening in Anaheim, California, last month.

Luis A. Huerta: Teachers College

Huerta is an associate professor of education and public policy at Teachers College, Columbia University. He has spent the last two decades researching various forms of school choice, such as charter schools, vouchers and tax-credit scholarships.

Growing fast: A former elementary school teacher, Huerta spoke about the rapid growth of charter schools, noting that today there are approximately 6,800 charter schools in 41 states. The first charter school opened in Minnesota in 1992.

More scrutiny needed: “Yes, some charter schools have been very successful, but there are many that have not been successful,” Huerta said “What hasn’t been looked at extensively are the teaching methods, the administrative processes and the process of getting parents involved that have been successful [in charter schools] and how to advance and replicate them successfully.”

On the management companies that run some charter schools: “The important thing to note is that these companies sometimes have no connection to the community where they are operating the charter and that goes counter to the intent of charter schools,” Huerta said.

Myrna Castrejón: Great Public Schools Now

Castrejón is the CEO of Great Public Schools Now, a nonprofit organization working in Los Angeles to identify and replicate successful public schools, both charter and district-operated.

Latinos in charter schools: “When we talk about charter schools in Los Angeles, we talk about our people,” Castrejón said. (Hispanics currently make up 51 percent of students enrolled in L.A. charter schools, according to the California Charter Schools Association.)

Too many failing: Castrejón noted that 160,000 students in the greater Los Angeles area are attending failing schools. Latino parents, she said, simply want their children to attend schools that will “open a path” to college and higher education.

Best practices: The goal, Castrejón said, should be to replicate successful models from any school that offers greater flexibility, including charter schools. This past summer, Great Public Schools Now conducted a poll that found 81 percent of voters agreed that “any parent with a child in an underperforming school should have the option of choosing a high-quality charter public school in their neighborhood.”

Louis Malfaro: Texas AFT

Malfaro is the president of the Texas AFT, a statewide teachers’ union that advocates on behalf of its 64,000 members.

Sending a wrong message: “The message is often that the charter schools are better than neighborhood schools, although there is no evidence,” Malfaro said. His group has noted that the most recent state standardized test results showed a larger percentage of Texas charter school districts and campuses rated “improvement required” when compared with district-run public schools. In 2017, 7.4 percent of charter school campuses were rated “improvement required,” compared with 4 percent of traditional public schools, according to the Texas Education Agency.

However, this data may not tell the whole story, since it does not factor in the demographics of students in both sectors. In addition, a study released in August by the Center for Research on Education Outcomes at Stanford University showed that “charter students in Texas experience stronger annual growth in reading and similar growth in math” compared to the gains of their peers in the traditional public schools the charter school students would have attended otherwise.

Teacher quality: “We know that teachers who work in charter schools have less experience, are younger and there is higher turnover” than in traditional public schools, Malfaro said during the panel. According to the U.S. Department of Education’s Schools and Staffing Survey, charter school teachers on average are 37 years old versus 43 years old for district-run school teachers, and have nine years of teaching experience compared to 14 years for traditional public school teachers. In addition, a San Antonio-Express News story noted the challenge Texas charter schools face in keeping teachers, while an Education Week story says the data on teacher turnover in charter schools is “remarkably muddled.”

Ernesto Cantu: IDEA Public Schools

Cantu is the executive director in El Paso for IDEA Public Schools, a nonprofit network of 61 charter schools enrolling more than 35,000 students throughout Texas. Cantu said one-third of students in IDEA Public School are English-language learners, 95 percent are Latino and more than 80 percent are from low-income families.

What Latino parents want from schools: “They look for security in their schools and for small classes,” Cantu said. “They want their child to succeed. … They want schools to pay attention to them.”

Demand exceeds supply: Cantu said IDEA Public Schools has a long waiting list at its campuses. (During the last school year, about 13,000 students were on waiting lists for San Antonio’s four largest charter networks — IDEA, KIPP, Harmony and Great Hearts Academies, according to data reported by the San Antonio Express News. IDEA plans to open nine new schools in 2018-19 including campuses in El Paso, San Antonio and southern Louisiana, among others.

College bound: “Our position is that 100 percent of our students will go to college,” Cantu said.

Family pledge: IDEA public schools requires families to sign a contract pledging to commit to a longer school day and more homework.