As Some Schools Drop Textbooks for ‘Open’ Resources, What’s the Cost?

Experts discuss the potential of OER, but also the challenges

Experts discuss the potential of OER, but also the challenges

Outdated textbooks with crumbling bindings often serve as a symbol of underfunded classrooms.

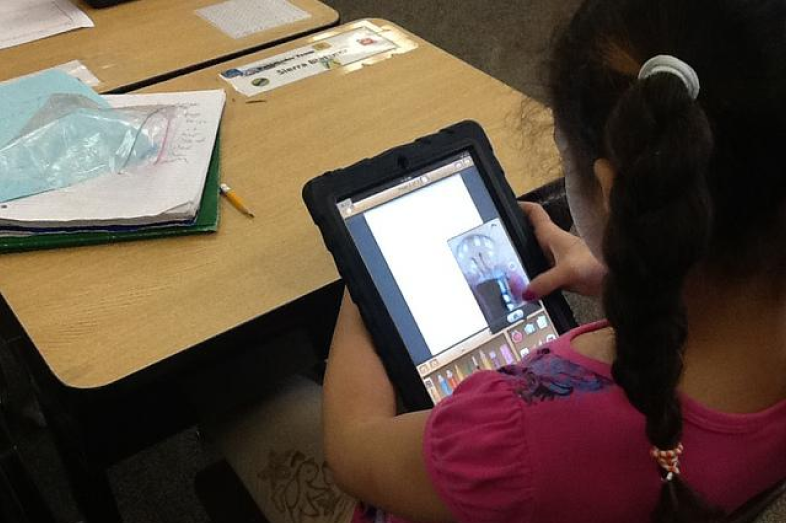

With the advent of open educational resources, educators have the ability update their curriculum in real time, for free — kind of.

During a discussion at the Education Writers Association’s national seminar in May, panelists advocated for the spread of free, digital, and easily updatable “open educational resources,” or “OER” for short. These materials can be anything from a supplement to an already written lesson plan or curriculum, to the entire curriculum itself, including reading materials, worksheets, and test questions.

But, the panelists warned, open resources come with a price tag.

“The content itself is free, but there are costs,” said Barbara Soots, who oversees instructional materials and open educational resources at the Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction in Washington State. “There’s cost in terms of printing; there’s cost in terms of teacher time.”

She added, “You’re still spending [money]; you’re just spending it in a different way.”

Over the past few years, as Education Week has noted, a number of nonprofit organizations, as well as state and local education agencies, “have begun creating openly licensed resources that they say will meet schools’ appetites for full platefuls of curriculum, covering entire subjects and grade levels, and not just slivers of them.”

The panelists said that there are many reasons a district might move to adopt OER wholesale, nixing the use of traditional textbooks for several courses at a time.

For one, said panelist Erin English, the director of innovation for the San Diego County Office of Education, these resources can potentially help students from different backgrounds “catch up” to other students. A student who has never traveled out-of-state can explore material about places that other children have traveled to with their families. A student whose family is American-born can read up on other cultures.

“It actually levels the playing field,” English said. “When you hand someone a textbook, that’s all they get. But when you hand somebody an OER, they can go down rabbit trails, they can fill in the gaps of their learning deficits.”

Soots noted that OER can pose new equity challenges, though.

“If we’re sending home materials to kids that they need to access on an internet device, then they have wireless access,” she said.

Stephen Noonoo, the K-12 editor for EdSurge, noted that the equity implications in higher education are even more obvious: College students often spend hundreds of dollars on textbooks a semester, and open educational resources allow them to save on materials, making participation more feasible for lower-income individuals, said Noonoo, who moderated the EWA panel.

Of course, said panelist Karen Vaites, if open materials are of poor quality — inaccurate, or just clumsily worded — they lose any benefits.

Vaites is a self-proclaimed evangelist of OER. In fact, her job title for Open Up Resources, a nonprofit OER curriculum developer, is “chief evangelist” as well as community development officer. But Vaites said she is only in favor of materials that surpass the quality of traditional textbooks, not imitate them for cheap.

Open-Up Resources was born when 13 states came together to figure out how to bring more curricula aligned to their standards to market for districts, she said — and that just because material is labeled as “OER” doesn’t mean it’s good.

Vaites urged reporters to look up the instructional materials used by local districts on EdReports.org, a nonprofit website that reviews them based on design, usability for teachers and students, and how well they align to state standards.

“It’s not interesting to us to bring free and above-average material to market. We want to bring free and excellent,” she said. “It’s not just free and open; it’s helping solve a material gap.”

Vaites said Open Up Resources, which is less than two years old, is self-funding, while still keeping all of their material free online.

Some funding comes from suppliers of other curricular supplements: If their curriculum includes a class set of “Esperanza Rising,” a novel for middle-grade students, Open Up will receive compensation. And although most of the materials are free digitally, Open-Up also charges districts for printing services.

English and Soots emphasized that in the districts they work with, adopting OER has meant extra work for teachers as they tailor the materials to their needs.

“You do have to put money into training,” English said. She added, “We have to honor teachers’ time, and make sure they’re being paid for their time.”

Vaites said that Open Up’s goal is to operate similarly to a textbook company, so districts don’t have to spend as much time adopting and adapting their materials.

But, for now, most open resources aren’t as comprehensive.

“Somebody had to create them, somebody had to post them on the internet, … and all of those have a cost associated with them,” Noonoo said.

Your post will be on the website shortly.

We will get back to you shortly