Have you heard about South Dakota’s social studies standards process?

It’s a never-ending saga that ties in with multiple cultural and educational wars seen in different communities throughout the U.S. Every education reporter should be following how states set standards in their coverage areas.

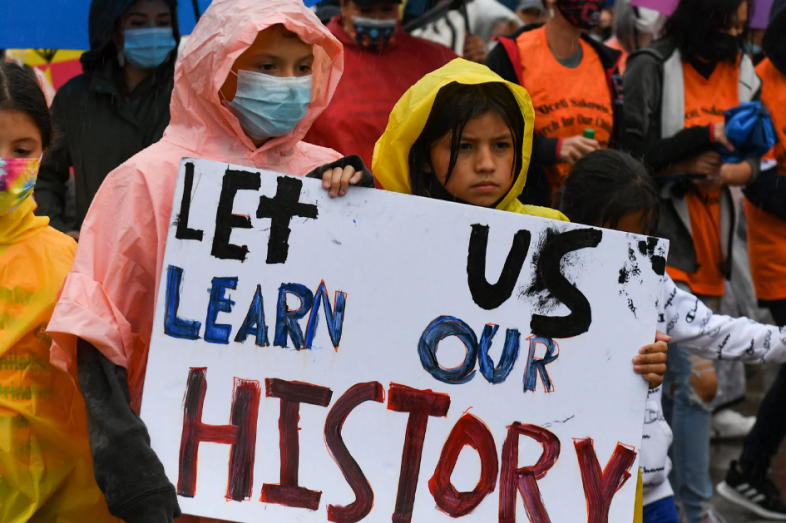

Issues like the one in South Dakota have popped up in book bans, so-called critical race theory (CRT) fights, divisive concepts bills and more. These changes are affecting all students, especially those who are LGBTQ+, Black, Hispanic and Indigenous.

Critical race theory is a college-level academic theory created by legal scholars and educators in the 1980s. The theory states that U.S. institutions – such as the criminal justice system, education system, labor market, housing market, and health care system – “are laced with racism embedded in laws, regulations, rules, and procedures that lead to differential outcomes by race.”

Some politicians have changed the long-standing definition of CRT for political gains, as Alia Wong, an enterprise reporter for USA Today covering inequities in education, has encountered.

Wong said she first started covering CRT debates in early 2021 when the idea was floated by conservative minds like Christopher Rufo “as a way of saying whites were being discriminated against,” Wong said.

“While I have covered debates over curriculum for a long time, the degree to which politics has intruded upon education really does feel unprecedented,” Wong said. “The level of polarization and almost viciousness has become very caustic in the debates. We do have a responsibility as journalists to accurately convey the extent to which those narratives are held by everyday people and also to scrutinize the implications of that politicization.”

She then noticed the term often, such as in bills attempting to ban “divisive concepts” from being taught in schools and universities.

It all boils down to how students are educated on the nation’s history, especially on topics like the removal or genocide of Indigenous people, and the enslavement of Black people. Opinions differ on whether students should hear the truth or whether they should be shielded from what some believe can be uncomfortable discussions.

How I Found the Story in South Dakota

Standards in every subject area and every grade level are required by law to be reviewed and revised on a cycle chosen by the secretary of the South Dakota Department of Education (SDDOE). It’s about every five to seven years in South Dakota.

Workgroups collaborate on the standards together: They bring a draft to the SDDOE, and the department puts out that draft for public inspection ahead of four public hearings across the state led by the South Dakota Board of Education Standards (SDBOES).

In 2021, social studies standards were on the calendar. A workgroup of mostly educators met in several sessions over the summer, in closed-door meetings, to come up with an initial draft before delivering it to the state education department.

I knew our process was coming up, and my original story on what the SDDOE had released that summer highlighted several references to “Indigenous Native Americans” broadly throughout the draft, and just three references to the Oceti Sakowin – the Seven Council Fires, or collectively the Dakota, Lakota and Nakota – the Indigenous people whose land South Dakotans occupy.

Shortly after I published that first story, a workgroup member sent me the group’s initial document and told me to compare it to what the state had released.

An easy find-and-replace search between the two documents showed the state had removed several references to the Oceti Sakowin from the group’s document. Essentially, the state had edited the workgroup’s work without their consent or knowledge.

Since my initial story on those changes, outcry came from the workgroup about Indigenous erasure; hundreds of public comments were submitted to the SDBOES against the changes; a protest occurred in our state’s capital, and several called for our governor, secretary of education, director of the Office of Indian Education, and the tribal relations secretary to resign.

Weeks later, our governor ordered the state to return to the drawing board for a second time, restarting the social studies standards revision process.

This year, now, the same conservative governor handpicked the workgroup. It includes fewer members, fewer educators and is being led by a facilitator from Hillsdale College – a private, conservative, Christian liberal arts college in Hillsdale, Michigan. Before the workgroup met to draft the standards, the facilitator sent packages to each of the members containing a document that would later become South Dakota’s draft social studies standards.

One of the workgroup members spoke out about the package because it didn’t originate with South Dakota educators and said it is close to the college’s “1776 Curriculum,” Hillsdale’s conservative response to The New York Times’ “1619 Project.” Top education groups in the state have questioned if the proposed standards are “age appropriate.”

Tips and Best Practices

Education reporters across the U.S. have reported on situations similar to the ones in South Dakota on their beats, whether it was with content standards or curriculum.

Remember, curriculum is the roadmap to teach to the content standards in any given subject, and curriculum decisions are local ones.

Here are some tips from myself and several other reporters who’ve covered stories like this.

-

Familiarize yourself with the current standards in your state early.

It’s important to be familiar with what’s in the standards or curriculum to know enough about it ahead of time, Jackie Hendry, host and producer of South Dakota Focus on South Dakota Public Broadcasting, said.

“Maybe you’re not a complete expert [in it], but you’re able to understand when someone’s saying something is in there that’s not in there, or when someone’s not as informed as they might lead you to believe about the nuts and bolts of what’s being talked about,” Hendry said.

Standards and curriculum should be public, Hendry noted, so track down where to find those or request copies of curriculum from your schools or districts. Most copies of proposed standards will be available on your state Department of Education’s website. You can also track down meetings of the Board of Education Standards in your state.

-

Look into how your state educates on Indigenous people and others.

Recognize the context of Indigenous history – and the history of other marginalized groups – in your state, too. Many of these issues on standards and curriculum have arisen at the same time as the U.S. reckons with the history of compulsory boarding schools that erased Indigenous cultures and led to generational trauma among Indigenous people.

“Especially in South Dakota, with a high population of Native Americans, many of the very historic markers of the conflicts between the United States and Native people during colonization, so much of that happened here,” Hendry said. “To me, I see it as perfectly sensical that we would have [Indigenous history] in our standards.”

Here are some questions to consider:

- Does your state or local district acknowledge that the state is on stolen Native land and which tribes the land belongs to?

- How do textbooks describe what happened to Indigenous people locally or statewide?

- Are students required to learn about modern Indigenous people and cultures?

-

Find your sources early, and balance their perspectives.

Reach out to workgroup members to keep tabs on their work, and be willing to talk off the record until they’re ready to bring up any concerns they have.

When you’re reporting, don’t just balance political interests, but also balance whose voices are centered – students, educators and non-educators.

Hendry noted not all politicians and policymakers are educators or experts on education.

For national reporters, Wong said it’s best to be proactive in finding sources because the best stories come from people who can tell you how issues are playing out on the ground, such as students who can explain how these issues affect their learning.

Students will always have a wiser take on politics in education than adults, Wong said, because the politicization of classrooms is happening because of adults, not because of students.

“How is this affecting the day-to-day?” Wong has asked students. “That question, the day-to-day, has often elicited the best story ideas, in my opinion, or the stories that seemed to resonate the most.”

Know when the meetings are: both the public hearings by your state’s Board of Education Standards, and the closed-door meetings the workgroup hosts when they draft new standards.

Be present at each of the public hearings, or at least listen remotely from wherever you are. It helps if you already know a majority of the people who are going to testify.

Also, keep checking your board’s page to see when written public comments come in. They make for good stories.

During this cultural moment, it’s important to know the difference between “CRT” and education that is historically accurate on race and history, as well as standards and curriculum, and inclusion and exclusion or omission.

Kristen Barton, education reporter at the Fort Worth Report, said most education reporters know, based on all the nonpartisan coverage on CRT, that it’s a college-level theory.

When people are upset about CRT, Barton said to ask them about what exactly is upsetting them, and to give an example.

“A lot of people think any mention of race in history can become CRT, and that’s not what it is,” Barton said. “Try to sort through the noise. That can help you find factual coverage and show what is really happening in schools. The more we can directly and factually say this is what kids are learning in school, the more you’ll move that conversation forward.”

Samantha Hernandez, education reporter for the Des Moines Register and a member of the politics team, said she works with the politics team to follow bills and legislation in Iowa and keeps an eye out on how those bills intersect with each other, and with more hyper-local issues like book bans.

She noted that no Iowa law actually bans the use of CRT.

“It was a big year for CRT and bills looking to ban that practice in K-12 and colleges, but what goes along with that is a hyperfocus on libraries and what books our students and youth have access to,” she said. “There’s a connection between that. A lot of experts will say that’s cyclical where you’re seeing larger public investments in what is happening in schools.”

The best thing to do when covering CRT and diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) topics is to go to local school board meetings, Hernandez said. See what’s happening and how people are reacting to various policies, she added, as well as make connections in your reporting.

“The background will get a little wide, but it’s important to show that these aren’t all isolated incidents,” she said.