How Will School Districts Leverage Stimulus Money for Summer Learning?

Here’s why reporters should follow summer school plans in 2021 and post COVID-19.

Here’s why reporters should follow summer school plans in 2021 and post COVID-19.

Summer learning programs are offered across the country each year by school districts. But following the massive disruption of education sparked by COVID-19, there’s more pressure — and federal funding — to get it right, with meaningful and engaging learning opportunities in the summer.

Districts have three years to spend their share of more than $120 billion in extra K-12 aid under the American Rescue Plan, a stimulus measure President Joe Biden signed in March. One percent of that federal aid was specifically earmarked for summer learning, though districts also have flexibility to use additional stimulus dollars to support their efforts.

Three education leaders shared insights during an Education Writers Association panel, titled “How Summer ‘School’ Will Look Different This Year,” at the 2021 National Seminar.

“There’s an urgent need for restorative and meaningful summer experiences for our young people,” said Ebony Johnson, the chief learning officer for Tulsa Public Schools in Oklahoma. “We’ve committed in an unprecedented way to investing in our young people and doing that this summer in a way that we’ve not done before.”

Johnson made clear that this won’t be the usual “summer school.” Oftentimes in the past, summer school “felt punitive; it felt like a mandate,” she said, though the district in 2019 took steps to revamp its approach.

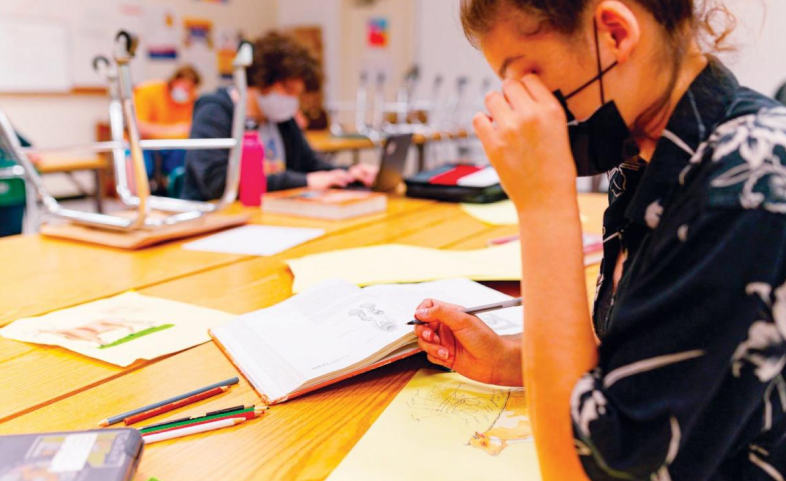

Credit: Peyton Sickles, staff photographer at the Chatham News + Record

This year, the design will be different, as will the scope (with more than double the number of students typically served in Tulsa), thanks to federal stimulus dollars. Each school in the district will host a summer learning program, but parts of the day will have the feel of a summer camp, according to the Tulsa schools official. (Here’s a link to the district’s summer learning website.)

“Half of their day will focus on that unfinished learning, the academic supports that are still needed,” Johnson said. “And then, the other half of their day will then, of course, open up for internships and STEM activities and clubs … the arts and robotics and chess and journalism.”

Aaron Dworkin, the executive director of the National Summer Learning Association, sees a tremendous opportunity to rethink summer programs on a broader scale, supported by a unique infusion of federal dollars.

“We have three years [to use] the funding,” he said. “That’s the real opportunity here,” to plan out meaningful programming over time, not just this summer, but in 2022 and beyond.

“The evidence base is really strong for what works” in summer learning, he said. “And we know what doesn’t work, too.”

Dworkin added: “The idea is to make it so exciting that it’s voluntary and everyone wants to come. ”

And it doesn’t have to only take place at school.

“Boston is a great example where they use the city as a classroom,” Dworkin said. “You have certified teachers working in programs at the zoo and the science museum, and cultural institutions running programs so students get out in their community.”

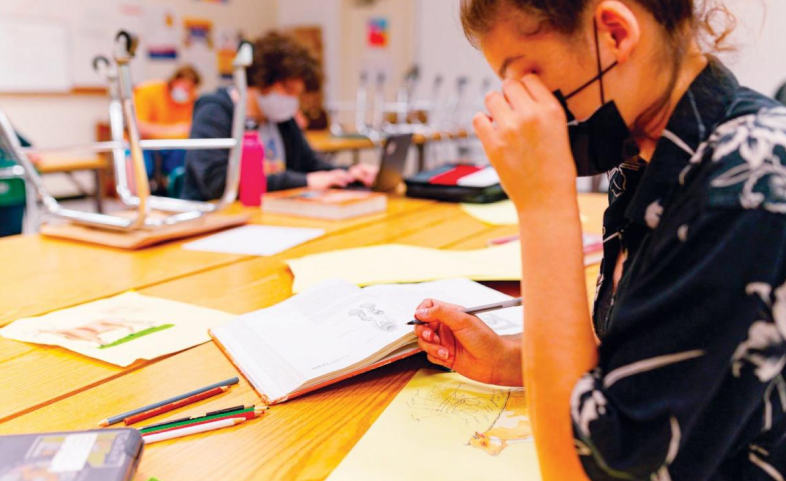

Credit: Peyton Sickles, staff photographer at the Chatham News + Record

It’s also important to understand how districts develop those plans, Peck said. “Is what they’re offering responsive to what kids in their community” really need? “And how do they know? How did they gather that information?”

Your post will be on the website shortly.

We will get back to you shortly