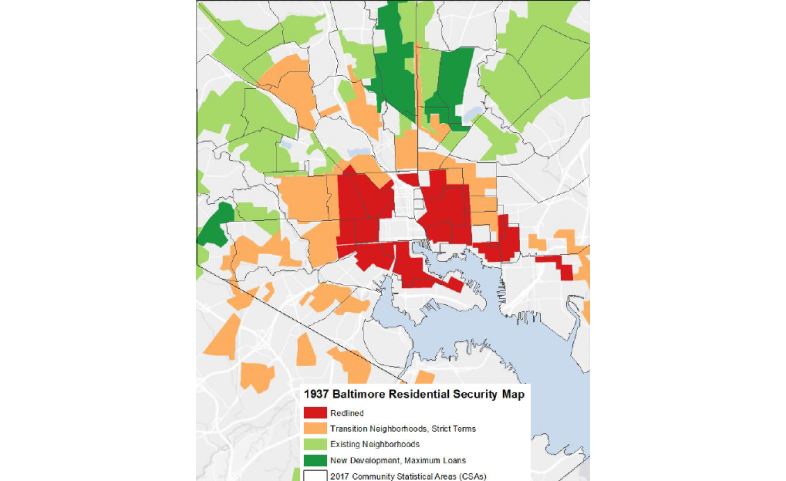

The segregated neighborhoods created in part by policies that barred predominantly black communities from federally subsidized mortgages were the same neighborhoods that today showed lower academic outcomes.

Santelises said those findings motivated her district to take a closer look at what kind of opportunities it provides students.

“I meet intelligent young people every day,” she said during a plenary discussion at the Education Writers Association’s 2019 National Seminar in Baltimore. “That’s not the question. The question is: Do they have the tools to translate their intelligence to navigating to success?”

She added: “If you can’t write well, that limits your access to certain rooms and certain opportunities.”

Santelises and the other panelists encouraged education journalists to report on districts and colleges that are moving the needle on student success, and cautioned against measuring that success solely based on test scores.

‘Not All That Counts Can Be Counted’

Andy Smarick, a researcher at the R Street Institute, a free-market oriented think tank, said he used to rely heavily on test scores, but realized that tests leave out critical information, such as whether or not students are prepared to be good citizens.

“Not all that can be counted counts. Not all that counts can be counted,” said Smarick, a former president of the Maryland State Board of Education.

Rucker Johnson, a professor of public policy at the University of California, Berkeley, said it’s important to recognize the ways segregation can influence student outcomes.

“We have to recognize that Baltimore, for example, is a place that is highly segregated, and it’s one of the reasons it has one of the lowest economic mobility rates. Segregation is not just isolating of people. It’s actually hoarding of opportunity,” like smaller class sizes and access to college-prep classes, Johnson said.

Santelises said one good way to measure student success is to compare it to real-life outcomes, as the Boston Globe did with its Valedictorians Project. The newspaper found that nearly half of the city’s valedictorians made less than $50,000 a year a decade after high school.

Removing Barriers

After comparing Baltimore’s educational outcomes to historical redlining maps, Baltimore City Public Schools made a systematic effort to place new gifted programs in minority neighborhoods. They were previously concentrated in whiter and wealthier areas, Santelises said.

“And lo and behold, what did we find? That we have (gifted) kids in every neighborhood,” she said.

Santelises said her strategy to help students succeed is to set high standards and then give students and teachers the support they need to meet those standards.

For colleges, it’s important to look at how many students are earning degrees, said Donna Linderman, an associate vice chancellor for academic affairs at the City University of New York.

Linderman said during the panel that CUNY started asking itself that question 12 years ago, after it realized half of its community college students dropped out by their second year.

“We started looking at what we were doing to help students navigate (college) and started looking at ways to remove barriers” such as financial concerns and lack of familiarity with college expectations, Linderman said.

CUNY’s Accelerated Study in Associate Programs (ASAP) is considered a model for its structural supports for struggling students.

From a wider policy standpoint, Johnson said that despite recent “amnesia,” research shows that desegregation, school funding reform and access to early childhood education have a huge impact on student success.

‘Children of the Dream’

“The synergies between them created landmark graduation rates,” Johnson said. A new book authored by Johnson notes that black students who attended racially integrated public schools had significantly higher educational attainment, including greater college attendance and completion rates. “And yet, when you go to our classrooms today, even though our kids are more diverse, the classrooms are as segregated as before Brown (v. Board of Education).”

Johnson’s new book, “Children of the Dream: Why School Integration Works,” looks at the generational impact of school integration in the 1970s and 1980s.

Smarick, who co-edited a book about rural education called “No Longer Forgotten,” said geographic location also influences what kind of access students have to opportunity.

Smarick said rural areas are similar to urban areas in experiencing higher concentrations of poverty, but there’s also “a view that outsiders want to come in and take over.”

Rural students are more likely to graduate from high school, but less likely to go to college than students from urban areas.

“In a rural community it’s not an idle worry that if everyone goes off to college, they won’t come back and the community will die,” Smarick said.