Six Story Ideas for Covering Race on Campus

College student body diversity, recruiting practices and history.

Journalists who want to better cover the reality of the racial environment on college campuses should broaden their focus beyond protests against Confederate statues or controversies over yearbook pictures, advised a group of researchers, educators and veteran journalists gathered at the Education Writers Association’s 2019 National Seminar in Baltimore.

The speakers on racial issues on campus outlined six main story ideas – some of which can be generated by freely available data – that would help reporters bring fresh ideas and responsible reporting to the fraught issue of race relations on college campuses.

1. First step: check student racial diversity

One simple way to initiate coverage of racial issues is to examine the diversity of each of your local colleges’ enrollments, according to Wil Del Pilar, vice president of higher education policy and practice at the Education Trust.

The 6 Story Ideas for Covering Race on Campus detailed below:

- First step: check student racial diversity

- How did the school get that way?

- Analyze the pipeline

- Follow the money

- Illuminate historical racism

- Investigate current racial climates and programs

The standard data used to report on the racial breakdown of college student bodies is available free from the U.S. Department of Education’s Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System, or IPEDS. (A quick video tutorial on how to use the database can be found here.)

The Education Trust also provides free reports that digest that data and can help reporters see who is – and who is not – represented on each campus, Del Pilar said. For example, Ed Trust’s March 2019 report Broken Mirrors examines equal access issues for black students on U.S. college campuses. A similar report on Latinx students is due out in June 2019.

2. How did the school get that way?

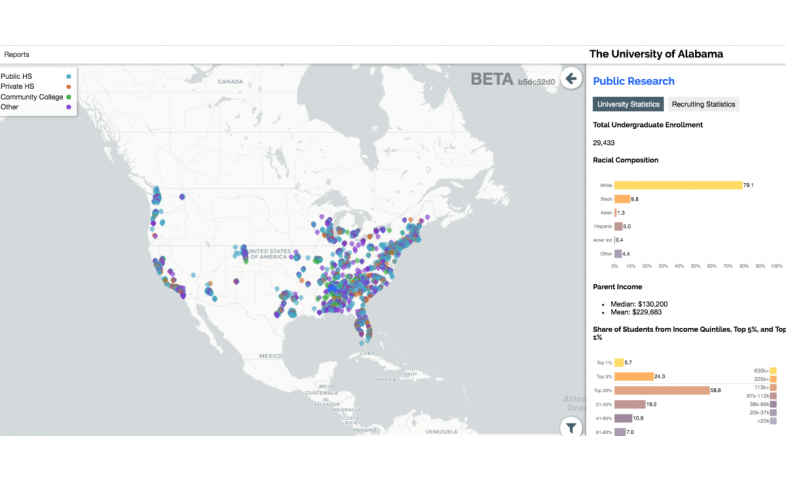

A great way to dig deeper into diversity at schools is to ask about the recruiting policies and actions that resulted in their student body mix, said Karina Salazar, a doctoral candidate at the University of Arizona who is studying college recruitment.

Reporters can generate stories on the efforts schools are making to recruit disadvantaged (or advantaged) students by using a new public database of high school recruiting visits being created by Salazar and Ozan Jaquette, an assistant professor at UCLA.

(More advice on admissions story ideas and new databases can be found here.)

The research by Salazar and Jaquette shows that most colleges – including many of the public colleges they’ve examined – tend to send more recruiters to high schools in wealthy and white neighborhoods. But, Salazar noted, universities that are serious about recruiting first-generation, low-income or students of color, “have quite an extensive tool kit to be able to do so.”

3. Analyze the pipeline

Those concerned with legacies of slavery and white supremacy on campuses should also be concerned about pipeline issues such as the reading levels of black children, and the preparation they receive in high school, said Freeman Hrabowski, president of University of Maryland, Baltimore County.

Ed Trust’s Del Pilar also recommended that journalists look at college advising practices and resources at high school campuses.

4. Follow the money

Even when states generously funded colleges, university enrollment “never looked like the population,” Del Pilar explained.

But financial issues are still worth investigating when examining inequities in college enrollment, said Salazar. She pointed to the relationship between declining state funding and increased “market-like activities” by public colleges, such as recruiting richer students who can pay high out-of-state tuition.

Salazar suggested reporters fact-check colleges’ claims that full-tuition students are needed to subsidize those who cannot pay full tuition.

5. Illuminate historical racism

Headlines are often generated by actions such as protests about statues of Confederate soldiers, or buildings named after racists, as well as when schools take actions such as removing a statue, changing a building’s name, or adding explanations or additional memorials to balance out the record.

But there are also opportunities for reporters to dig into other ways colleges are dealing with histories of racism, said Kirt von Daacke, an assistant dean at the University of Virginia. He is co-chairman of Universities Studying Slavery, a coalition that he calls a “support group” of schools looking at their institutional history with slavery. Some of the staff at the member schools are considering how their endowments and prestige are rooted in a history of white supremacy, he said.

Von Daacke and Hrabowski noted that reporters in states with less obvious historical connections to slavery and institutionalized racism can still highlight how their universities have nevertheless perpetuated cultural disparities, even if their bricks were not put in place by slaves.

Von Daacke urges colleges to invest in faculty-wide training in a university’s history, so that it can be disseminated throughout the culture, not just through students interested in social sciences. This could have the benefit of ensuring that the memory is not lost, something Hrabowski cautioned against.

“We can’t forget what has happened to people here,” Hrabowski added.

6. Investigate current racial climates and programs

The experiences and success of students of color on campuses are also important indicators of racial climate, said Hrabowski. One way to document that: outcomes measures such as graduation rates for students of color. (Data on graduation rates by race and gender are available through IPEDS and Ed Trust’s Collegeresults.org site.)

In addition, some colleges, such as Georgetown University, are taking actions to address conflicts or racist legacies by, for example, offering reparations in the form of admission offers or other programs.

Journalists should do reality checks on whatever efforts colleges tout as evidence of progress on racial strife, said Hrabowski. Any solutions should be tied to real action and real outcomes, he said. Rather than sticking to the university public relations department, check with families and students about their lived experience at the school.

One way to gauge how serious the college is about addressing racism: check what’s getting funded.

“It always involves money,” von Daacke said.