Monitoring racial achievement gaps helps effectively measure educational equity. It became a major focus of education with the enactment of No Child Left Behind in 2001. To document the gaps, reporters must look beyond overall proficiency rates in a state, school district or school and dig down into test scores as they are reported among individual student groups. Reporting this helps to put pressure on schools to address inequities.

In 1969, the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) began administering tests. The organization has measured achievement gaps among different student groups. It found that white students outperformed other student groups, such as Black and Hispanic. Since the 1970s, those racial achievement gaps have narrowed substantially in both reading and math in most states as Black and Hispanic student scores have increased faster than white students. Data on the gaps varies from state to state

NAEP data over time has also shown racial gaps between white and Asian student groups, with white students underperforming.

The COVID-19 pandemic has erased some of the gains. The September 2022 NAEP report, measuring the progress of 9-year-olds in math and reading during the pandemic, showed overall drops in scores of seven points in math and five points in reading as compared to 2020. But when broken down by subgroup, Black students saw a 13-point drop in math, and Hispanic students an eight-point drop as compared with a five-point drop for white students.

How to Report on Achievement Gaps and Opportunity Gaps

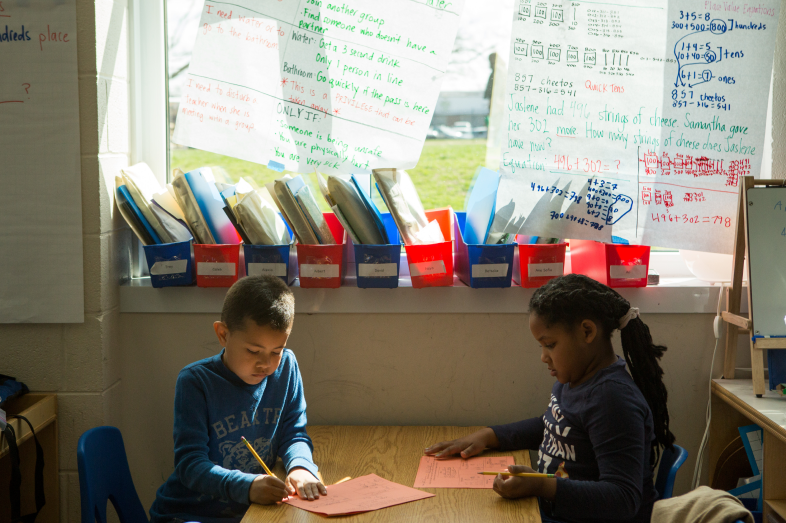

Reporting on achievement gaps helps to ensure states, districts and schools provide an equitable education to all student groups, especially due to the underfunding of school districts with majority students of color.

But it’s essential not to focus on achievement gaps in a way that gives the perception that certain groups are behind their peers.

In recent years, focus has expanded to include examining the academic growth of students who have not tested proficient. Strictly measuring proficiency rates – which are generally state standards – doesn’t take into account where a student was at the beginning of a school year. A student who is advanced may be considered proficient but show no growth in knowledge while a student who started the year at a deficit may have significant academic growth but still not reach proficiency. Steady growth is expected to lead to proficiency, though not always in the course of one school year.

Another focus shift is away from the term achievement gap and instead using opportunity gap to explain the lower test scores of some student groups. It’s a recognition that students in lower-achieving groups often come from low-income families and don’t receive the resources or opportunities to succeed at the same rate as their wealthier peers.

Data also shows Black and Hispanic students attend high-poverty or mid-to-high poverty schools more than white students. Additionally, students of color attend high-poverty schools the most based on student eligibility for free or reduced-priced lunch.

Other factors that could affect achievement gaps are the quality of early childhood education, the quality of public schools and state policies.

Similar results show up in average SAT scores and average ACT scores with Asian students scoring the highest, followed by white students; students of two or more races; and students who are Hispanic, Pacific Islanders, American Indian/Alaska natives, and Black. Keep in mind that SAT and ACT are voluntary tests. The scores tend to go down as participation goes up.

Racial gaps also appear in the Advanced Placement exam results, though the College Board quit posting scores by race and ethnicity in 2021. What contributes to these gaps is that students from low-income families can’t afford tutoring and retaking tests multiple times. AP’s benefits “have so far flowed disproportionately to white students in affluent school districts.”

Additionally, Black, Indigenous and students living in rural areas have issues accessing AP coursework, and Black students may be “consistently under-enrolled in AP,” even when the courses are available.