Why It’s So Hard to Report on Schools While Home-Schooling During a Pandemic

One journalist shares her struggle to report while guiding her son with autism through school.

One journalist shares her struggle to report while guiding her son with autism through school.

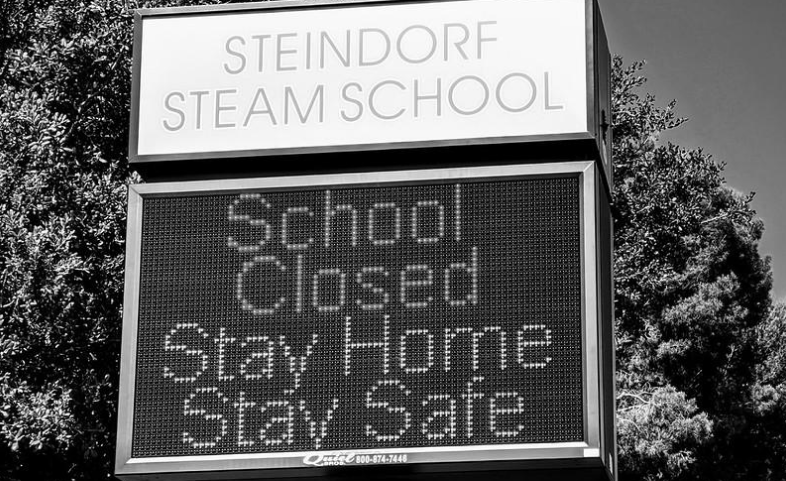

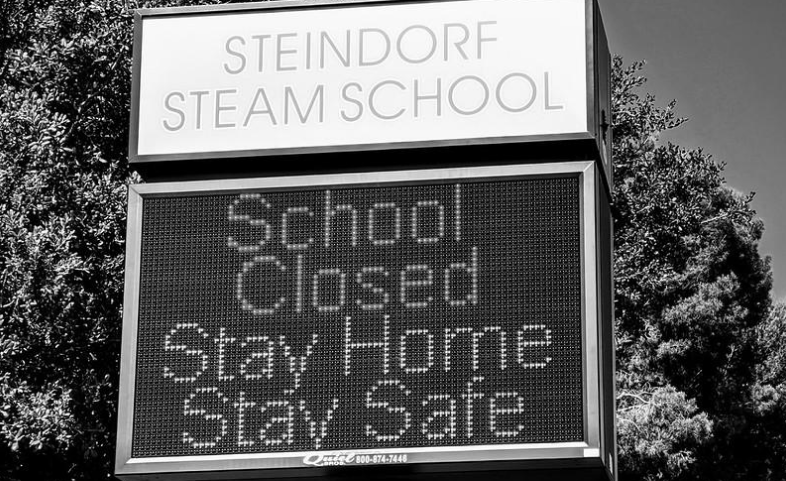

With a college kid rooting around the fridge for yet another meal, a husband conducting loud Zoom meetings about two feet from my desk, and a teen with autism freaking out from a lack of structure, 2020 is not shaping up to be a banner year for productivity as a freelance education writer. I only published two pieces since the schools were shut down in March.

Across professions, working parents had a tough spring as they attempted to do their jobs while reviewing math facts with their 7-year-olds and building Legos with toddlers. One survey found that the average parent spent 13 hours per week helping their children with their schoolwork this spring. Experts say that this burden has fallen most strongly on women, with many speculating that this new load may set a generation of women permanently behind in the workplace.

If I were going through this alone, I would have adjusted to the “new normal” eventually. But the school closure was particularly tough on my son with autism. I struggled to find blocks of uninterrupted time to get into the flow of writing when so many hours were spent filling in the vacuum that school left. I questioned my ability to continue to write about schools objectively, given our family’s experiences. Despite these difficulties, I am more committed to my career more than ever, because this pandemic has shown a bright light on the vital role that schools play in our society and economy, and how writing about education and children matters.

Starting that second week of March, I no longer had full days of total tranquility to work and catch up on chores. Suddenly my house was a three-ring circus, with children and adults all working on the WiFi simultaneously and demanding vast quantities of food three times a day. My husband and college kid adjusted to working and studying from home effortlessly, but the high school kid (who has autism) had more trouble without the interruption in schooling. At most, he had one hour of live online classes per week with no predictability or dependable schedules. He missed his teachers and classmates quite a bit.

Like many kids on the spectrum, my son is a creature of habit. Even though he’s high functioning enough for a mainstream school, he became very anxious without the routine, schedule, and rules of a typical school day. These anxieties then triggered persistent verbal tics, which plagued him and our family. We tried to ground him by creating our own family schedule with daily activities — It’s 11:30! Time for Family Yoga! — and with tutors who chatted with him online during the week.

Since kids with autism have few friends, my son hasn’t interacted with a peer since school ended in March. Watching his social skills regress in real time, I worry that he may be very odd when schools open in a few weeks.

I am sure that my son’s academics slipped during the spring; research shows that most students, particularly low-income students and those with fewer hours of live education classes, suffered a significant regression in the academic skills. But we are most concerned about his social/emotional needs and social skills. A recent CDC survey found that the pandemic was having a major impact on the mental health of young people, and we could definitely see its impact in our house.

My main job this spring became helping my kid manage this major change in his life. I was afraid to commit to an article with a tight deadline on top of everything else on my plate. I was feeling rather raw about having to dump two weeks of reporting in March on a suddenly irrelevant topic. Instead, I squeezed in alternative forms of writing and professional development in the spare moments of the day. I also advocated for the special needs community in town by creating a space for them to network on social media and by regularly talking of their needs at school board meetings.

Through my advocacy work, I learned from these parents about the variety of problems facing other parents of children with special needs. Back in March, I wrote in USA Today that students with significant disabilities would have a hard time without in-person therapies and might not be able to focus on a computer screen independently, but now I believe that school closures caused them and their families more significant difficulties. Parents tell me their autistic kids have become more autistic and developed new behavioral problems. Parents of children with disabilities, like dyslexia and ADHD, explain that they do not have training to help them with their unique learning and attentional needs and feel overwhelmed.

It’s totally normal for a parent to feel upset when their child struggles. I developed rather “strong feelings” about how my son’s school should manage the shutdown so that kids like mine wouldn’t feel so abandoned and that mothers could maintain careers. I questioned whether I could remain an impartial observer of events and report on education issues fairly, now that I was a direct deliverer of education; a reporter can’t report on a NASCAR race while driving a car in the race at the same time. Luckily, I was assigned an education topic in May that was only tangentially related to the pandemic and connected me to a truly inspiring teacher, who renewed my passion for this issue.

Despite these challenges to my professional productivity, I have never been more proud to be an education writer. Schools have been front page stories for a reason. We need them. Without schools, the economy grinds to a halt and the most vulnerable are not educated. Many of us spent more time as teachers and counselors this spring than actually writing about teaching, but I’m certain that these experiences will deepen our reporting and questions in the future. I think our best writing is yet to come.

Your post will be on the website shortly.

We will get back to you shortly