There’s no one way to get a great data story on the education beat. You can start with a hunch, dig for data, and then humanize the story with on-the-ground reporting. Or you can start with the people and work back to the data.

Stellar journalists described both of these approaches at a recent Education Writers Association event, in a session called “How I Did the (Teacher) Story.”

Ricardo Cano (formerly with The Arizona Republic and now with CALmatters) and Juan Perez, Jr. of the Chicago Tribune used data as a starting point for their reporting projects.

At the EWA seminar, the two journalists explained how they collected public documents and data to quantify alarming problems — the teacher shortage in Arizona and sexual abuse suffered by Chicago Public School students, respectively. After organizing that data, they set out to finding people affected by those problems and persuade them to speak on the record.

Cano and Perez shared tips about the types of info reporters could ask for to do their own stories on these issues.

Cano sent 200 record requests to Arizona school districts seeking teacher directories and certification documents — a potential treasure trove available in every state. About 160 districts responded to his request, Cano said. After processing the data, he sent it back to each district to fact-check, in order to avoid later corrections.

What he found was that more than half the schools employed teachers who had certificates that didn’t require formal training, and at least 40 teachers were relying on emergency substitute licenses, which require only a high school diploma.

Cano’s story included poignant narratives of administrators struggling to recruit teachers, and rookies struggling to teach. He also provided an online, searchable database so that readers could find out how qualified teachers are at their own neighborhood schools.

Exposing a District’s Systemic Failures

Perez was part of a four-person team that uncovered hundreds of instances in which Chicago Public Schools failed to detect, prevent, or respond to sexual abuse suffered by students, often at the hands of local CPS teachers or staff. Like Cano, the Tribune team sent their findings to the central office at Chicago Public Schools to give the district a chance to respond.

Almost anywhere else, just one such incident would’ve made a big story. But in the Chicago district — the nation’s third-largest school system — the number of victims and abusive or negligent adults was simply staggering. The project reads like an encyclopedia of horrors.

In his presentation, Perez didn’t dwell on individual stories, but instead ticked off a litany of holes in the safety net meant to protect students: inadequate background checks for teachers and school staff, no protocols for reporting sexual abuse on campus, no mechanism to ensure that school staff actually contact child protective services about suspected incidents of abuse, no consistent training for school staff, and a compliance hotline where the voicemail was full and no one ever answered the phone.

The Chicago Tribune project has already resulted in policy changes, personnel changes, and an endless supply of nightmarish follow-up stories like this one. For anyone else wanting to dig into similar subjects, Perez shared a detailed tip sheet.

Reporting in a ‘Circus Atmosphere’

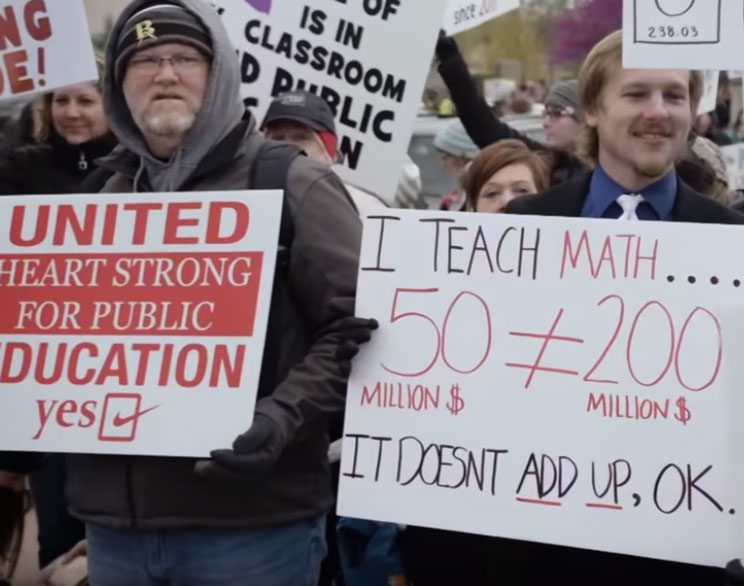

But while Cano and Perez gave us the stories behind carefully-planned projects, Andrea Eger of the Tulsa World provided a glimpse into what it’s like to cover the education-beat equivalent of a hurricane — a massive statewide teacher walkout that lasted 11 days, bringing swarms of national media parachuting in to flyover country.

Having covered the education beat since 2000, Eger read the forecast and knew a storm was brewing. But she had no way of predicting how big it would be, how long it would last, or what the landscape would look like in its aftermath. And of course she had no control over the story’s ebbs and flows.

The “circus atmosphere” was “exhausting,” she said. Eger described the experience as “one of the hardest slogs of any slog I’ve ever slogged in two decades” of covering education policy.

To set Tulsa World’s coverage apart, Eger and her colleagues focused their enterprise efforts on providing context and background about what led to the walkout. Instead of treating it as “an event,” they showed it as the culmination of more than a decade of fatigue and frustration due to state aid cuts, with consequences that just kept compounding.

They produced stories showing that low teacher pay in Oklahoma had led to the state “hemorrhaging teachers” to the point that schools had begun relying on personnel with “emergency certification” — previously so rare that a superintendent would have to appear before a state agency to plead each individual case. Remember that story Time magazine had on the teacher selling her plasma? Eger had the story with Oklahoma teachers three years ago.

During the walkout, Tulsa World also introduced voices of brand new leaders who sprang up overnight out of social media posts gone viral. “It helps for people’s understanding to make things personal,” Eger said.

Tulsa World also included teachers from schools where teachers voted not to participate in the walkout — an angle few other media outlets covered.